FBI, DOJ want companies to back off end-to-end encryption

IDG NEWS SERVICE: The agencies want tech vendors to retain access to encrypted data to comply with court-ordered warrants

U.S. tech companies should retain access to the encrypted information of their customers, instead of providing end-to-end encryption, in order to give police the tools they need to investigate crimes and terrorist activity, two senior law enforcement officials said.

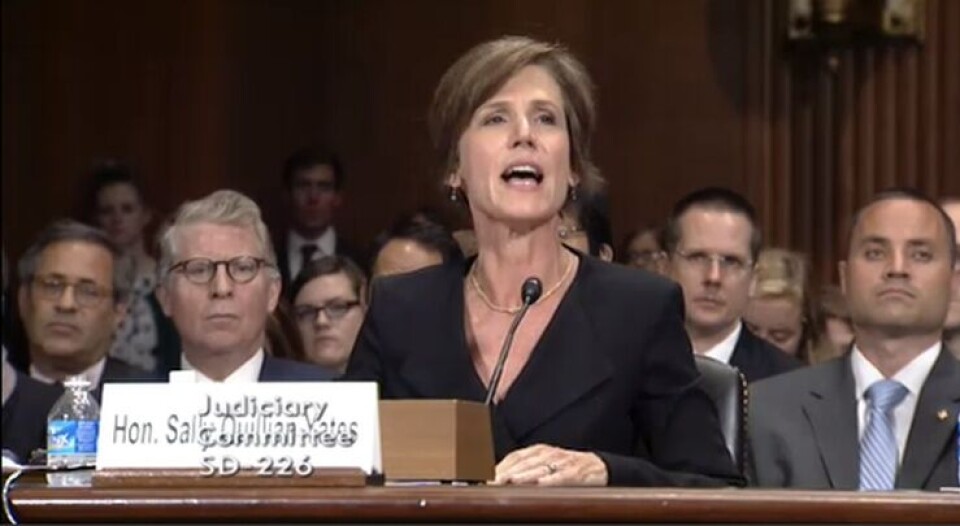

The U.S. Department of Justice and the FBI aren't seeking new legislation to require tech companies to comply with warrant requests, at least for now, and they don't want companies to build encryption back doors that give the agencies direct access to communications and information stored on smartphones, said Sally Quillian Yates, the DOJ's deputy attorney general.

Instead, the DOJ and FBI, in their continuing efforts to combat the use of encryption by criminals and terrorists, are proposing that tech and communications companies retain internal access to encrypted information so that they can comply with court-ordered search warrants, she told the Senate Judiciary Committee Wednesday. Several tech companies already retain some access to customers' encrypted data, she said.

Legislation may eventually be necessary, but the DOJ is now looking for voluntary compliance from tech companies, she said.

With new encryption services from tech companies, "critical information becomes, in effect, warrant-proof," Yates said. "We are creating safe zones where dangerous criminals and terrorists can operate and avoid detection."

A recent push by tech companies toward end-to-end encryption, partly in response to reports of mass surveillance programs, has led the DOJ and FBI to raise concerns about law enforcement agencies "going dark" when investigating crime. Last September, FBI Director James Comey Jr. first questioned decisions by Apple and Google to offer encryption by default on their smartphone operating systems.

"The world has changed in the last two years," Comey told senators. "Encryption has moved from something available to something that is the default, both on devices and on data in motion."

Terrorist group ISIL (Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) has used encryption effectively, Yates said. ISIL makes first contact with many potential recruits on Twitter, where the group has about 21,000 followers of its English language feed, but then directs them to communicate further on an encrypted messaging service, she said.

"This is a serious threat, and our inability to access these communications with valid court orders is a real national security problem," Yates added. "We must find a solution to this pressing problem, and we need to find it soon."

U.S. tech companies should be able to find a way to provide law enforcement access to encrypted data and still provide many of the security and privacy benefits of encryption, Comey said. "The tools we are being asked to use are increasingly ineffective in our national security work and in our criminal work," he said. "I don't come with a solution -- this is a really, really hard problem."

But Comey also rejected arguments by some computer scientists who say it's impossible to allow police access to encrypted data without also opening it up to hackers.

"I think Silicon Valley is full of folks [who] have built remarkable things that changed our lives," he said. "Maybe this is too hard, but given the stakes ... we've got to give it a shot."

While companies like Google and Apple were not included in the hearing, senators gave a mixed reaction to the testimonies of Yates and Comey. Some senators suggested it would be nearly impossible to prevent foreign tech vendors from offering encrypted communication products.

Senator Al Franken, a Minnesota Democrat, pressed Yates to provide statistics about the number of criminal cases affected by encrypted data.

Before creating new regulations, Congress needs to have a "clear understanding of the scope and the magnitude of law enforcement's security interests," Franken said.

Yates couldn't provide a number of cases affected, saying it was difficult because, in many cases, police don't seek a warrant when they know the information they want is encrypted. But Cyrus Vance Jr., district attorney in Manhattan, told senators his office has tried to pull data off 92 Apple phones running iOS 8 in the past six months, and on 74 of those devices, the data was encrypted.

Other senators were sympathetic to the encryption dilemma faced by law enforcement agencies. Senator John Cornyn, a Texas Republican, pressed Comey to tell lawmakers that U.S. residents will die if a solution wasn't found. Comey declined, saying he doesn't want to scare people. The FBI will do the best job it can with the crime-fighting tools it has, he said.

Still, Cornyn questioned companies that offer encryption without retaining some access to the data. "It strikes me as irresponsible, and perhaps worse, for a company to intentionally design a product in such a way that prevents them from complying with a lawful court order," he said.

Grant Gross covers technology and telecom policy in the U.S. government for The IDG News Service.